With a population roughly twice that of the United States, the region’s epidemic momentum has now eclipsed previously hard-hit places like Latin America and India, with cases surging 41% in the world. over the past week to more than half a million, according to Bloomberg analysis of data from Johns Hopkins University. Deaths increased 39% in the seven days to Wednesday, the fastest rate in the world, and will likely rise further as an increase in the number of deaths usually follows an increase in the number of cases.

Growing crisis

Meanwhile, the overall vaccination rate of 9% in Southeast Asia lags developed regions like Western Europe and North America – where more than half of the population has received vaccines – and exceeds only Africa and Central Asia.

As large parts of the developed world reopen their doors to business, the deteriorating situation in much of Southeast Asia means they are reimposing the brakes on movements that undermine growth. Singapore is the exception, where sealed borders and high vaccination rates keep the virus contained in the region’s only developed economy.

The region’s stocks and currencies have sold off in recent weeks, as governments are forced to explode budget deficits and central banks run out of ammunition. It comes as the US Federal Reserve embarks on preliminary discussions on curtailing asset purchases, reducing the room for maneuver for Asian policymakers to ease policy further without risking weaker currencies.

Leaders and laggards

“Given the slow pace of vaccinations, with the exception of Singapore, we expect the recovery to be bumpy, and the risk of further periods of increased restrictions remains,” said Sian Fenner, senior economist for Asia. based in Singapore at Oxford Economics Ltd. “Rising uncertainty is also likely to lead to further economic scars.”

Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest economy, topped India in the number of new daily cases this week, consolidating its position as the new epicenter of the Asian virus, while several of its neighbors also record a record number of cases.

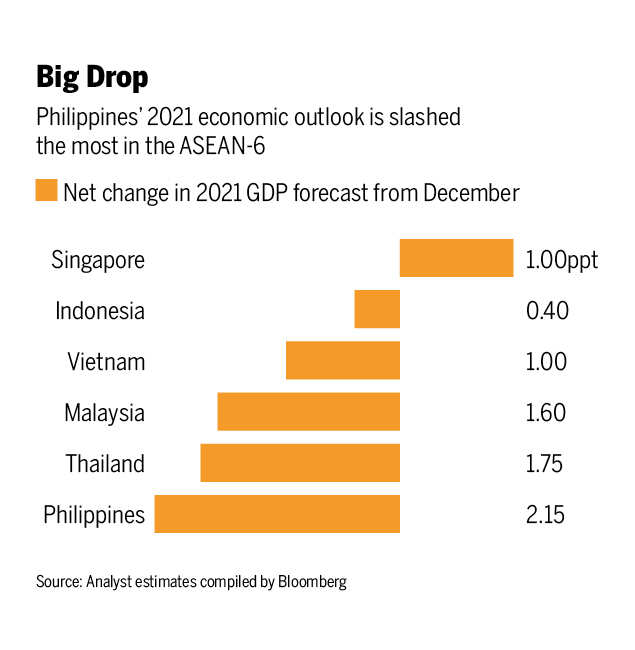

Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines have already cut their gross domestic product forecasts for this year, and Malaysia says it will soon follow suit. Vietnam, one of the few economies in the world that continued to grow strongly last year, has exceeded forecasts for the first half of 2021 and is now grappling with an epidemic in areas that are home to large industrial parks.

Before the pandemic, Southeast Asia’s largest economies combined would have been the fifth in the world, behind Germany, according to World Bank data.

Southeast Asia has been supported by strong global demand for exports, especially electronics, as the pandemic has undermined traditional drivers such as consumption and tourism. This external demand could change, however, auguring further pain for the region.

“Now that the advanced economies of the West are reopening, their demand dynamics are likely to shift from goods to services, implying that Asian export growth is likely to slow in the coming months,” said Tuuli McCully, head of Asia in Singapore. Pacific Economics at Scotiabank. “For the economic recovery to stay on track, domestic demand should pick up, but the worrying virus situation is dampening that outlook. ”

Led by Vietnamese stocks, the MSCI Asean Index fell 1.7% this month, prolonging its decline of 3.4% in June. The Thai baht, the worst performing currency in emerging Asia this year, has lost around 5% since mid-June, around the time the delta variant appeared in the country, while the Philippine peso has lost 4.2%.

In a note Thursday, economists at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. said they were slashing second-half growth forecasts by 1.8 percentage points on average across Southeast Asia, with the biggest declines for Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand.

New epidemics and tighter restrictions “are expected to weigh much more on second-half GDP growth than we previously estimated,” economists said.

Big drop

This comes as key interest rates in the region are at or near their lowest and governments find themselves with limited space to spend more.

Malaysia, which has already adopted four stimulus packages this year, says it plans to raise the debt ceiling as it lacks fiscal space. Indonesia recently hinted that it might not get the budget deficit under control as quickly as expected, after raising the legal limit last year. The Philippine government, which just repaid a 540 billion pesos ($ 10.8 billion) central bank loan last week, immediately did an about-face and called for another.

The need to increase stimulus spending, while simultaneously lacking revenue means “a more difficult start to fiscal consolidation for these governments after large deficits in 2020, and in many cases weaker fiscal performance this year than expected, “said Andrew Wood, a Singaporean. analyst for S&P Global Ratings.

In its recent decision to downgrade the Philippines’ credit rating outlook to negative, Fitch Ratings noted that the pandemic is creating potential “healing effects†that could dampen growth in the medium term. S&P issued a similar warning to Indonesia on Thursday, saying the Covid-19 outbreak and the extended lockdown had material implications for the economy and would reduce credit rating buffers.

“False compromise”

Rob Carnell, head of Asia-Pacific research at ING Groep NV in Singapore, said poorer countries in Southeast Asia that tried to limit lockdowns at the start of the pandemic to mitigate the impact on people’s livelihoods are paying the price for this choice – mainly because their efforts to test, trace and isolate positive cases were ineffective. As a result, countries like the Philippines and Indonesia that have opted for partial and gradual lockdowns have been forced to sue them in one form or another.

“It was easier for rich countries to lock in and pay people to stay at home or be put on leave while working, and the poorest tended to try to negotiate the restrictions with the opening to limit the blow to GDP, “he said. .

“Of course, it was a false compromise – at best a short-term compromise,†he said. “We may now be starting to see the ramifications of such policies. ”