A few years ago, Frank Taylor moved his hair salon to First Hill, after being relocated by the redevelopment of 23rd Avenue and Jackson Street. Then he was sidelined by prostate cancer and frequent medical treatment. Afternoon traffic stinks. Yet it still serves customers who manage to drive or walk to Madison Street.

Now he and his neighbors are worried about another hardship, when city contractors this month begin tearing down Madison to build the RapidRide G Line the voters of the bus corridor approved in 2015. Eventually, they will reach the Taylor block between Terry and Boren avenues.

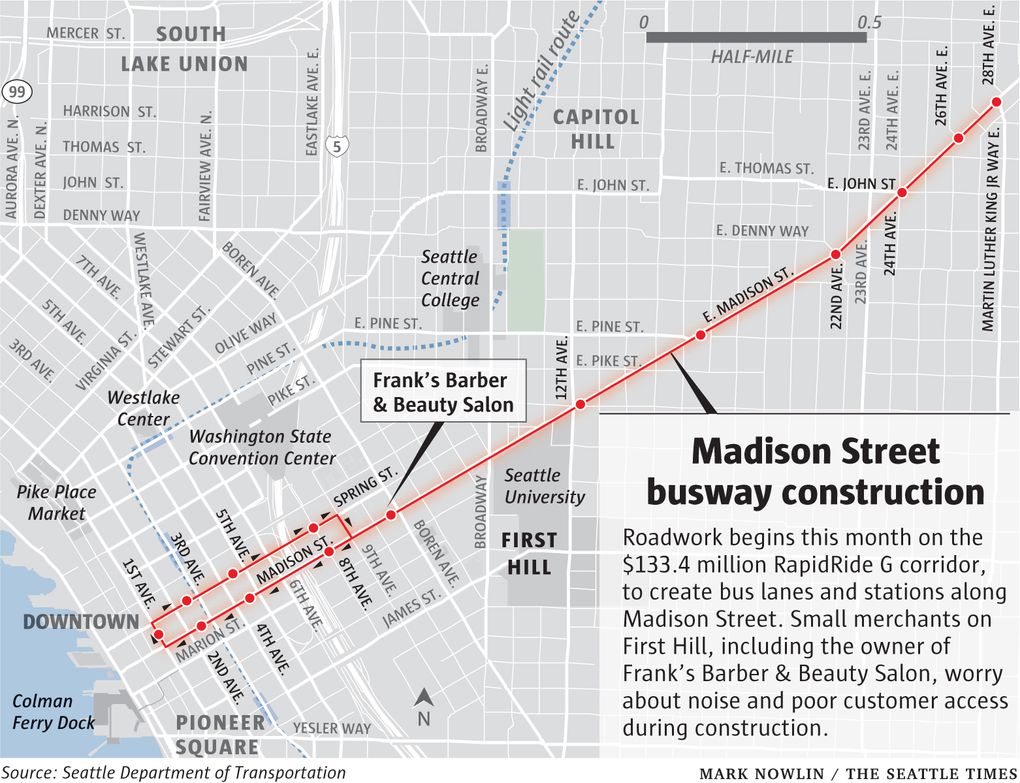

The $ 133.4 million project is designed to serve 12,000 daily passengers, on a direct route from First Avenue to Martin Luther King Jr. Way East, which is due for completion in 2024. Buses would arrive as often as six minutes from the start. ‘interval at peak times, using the bus- only lanes. Passengers can save five minutes per trip.

The job involves breaking up the pavement, pouring new concrete that will withstand 45,000-pound buses all day, and replacing crumbling sidewalks. The Seattle Department of Transportation promises to communicate and maintain access for walkers and drivers, but past road reconstructions have plagued small traders on 23rd Avenue, and when Sound Transit added rail tracks to Martin Luther King Jr. Way South.

“They don’t care about these companies, that’s how I feel. It’s going to be chaotic, â€predicted Taylor, between two strokes of an electric razor near the ears of a young man.

“People are going through a difficult time like this with COVID. Now you throw that in here, and some of these guys aren’t going to make it happen.

Four companies and two supporters of the Taylor Block, between Boren Avenue and Terry Avenue, wrote to Mayor Jenny Durkan asking for subsidies for losses during construction.

“Lack of action will result in the loss of many beloved businesses. While we as a city are to honor our dedication to equity and inclusion, city council did not respond to our initial petition for relief and we call on your office to act now, †said the letter.

SDOT held a groundbreaking meeting on September 30 with federal transit administrator Nuria Fernandez, whose agency provided $ 80.5 million in grants. Construction begins this month at downtown First Avenue and on Madison near the University of Seattle.

The city has not announced a date to reach Block 1000, outside Frank’s Barber & Beauty Salon, where traders could have a few months before the jackhammers arrive.

“It’s good,” said neighbor Thanh Thu Le, co-owner of Pho Saigon, who is not yet prepared for the noise and dust. Her clientele of nurses and other medical staff at Swedish medical centers and Virginia Mason prefer to sit inside rather than buy take-out.

“The construction is going to make things really difficult. They want to sit down and relax. We’ll stay open, but I don’t feel like we’ll be full of customers like we used to, â€Le said. But she said she believes the RapidRide line will improve her customers’ travel options in the long run.

Mikell Baccus of Anderson’s Comfort Footwear wonders if customers at his store, including elderly people with foot injuries, will still be able to get to the store from the sidewalk or if relatives will find a place to drop them off nearby.

SDOT promises “in most cases a gateway will be maintained on at least one side of the street. “

Cars will be diverted onto a single lane in each direction in construction areas. The curbside parking will be permanently removed from the overcrowded blocks to create space for bus routes and stops in the center of the road.

Taylor assumes 55% of his customers are driving. Others use carpooling services, walk from nearby apartments, or take a bus.

The Madison Merchant Letter calls for payment for “quantifiable costs” such as lost sales and higher parking costs as curbside space is reduced.

In the mid-2000s, Sound Transit was promising exceptional sensitivity to the ethnically diverse community along MLK Way, but the work took a year longer than expected and even sparked utility outages. The Rainier Valley Community Development Fund provided marketing assistance as well as millions of grants for “business disruptions†when traders proved through monthly receipts that they had lost income. Some have moved away or withdrew.

A decade later, the city’s 23rd Avenue reconstruction project hampered small businesses in the once-predominantly black central area. The administration of then-mayor Ed Murray said it could not offer relief money, but political heat increased, including a complaint from the NAACP about gentrification, until what the city sets aside $ 650,000 to help small businesses.

Taylor said he was one of several merchants who received $ 25,000 each. “People just had to walk through a maze†to get to his store and some customers suffered from asthma flares, he recalls.

SDOT says it has no plans to compensate Madison Street businesses. “The Washington State Constitution prohibits donation of funds from government to business or private party, â€a spokesperson said. The agency called the 23rd Avenue payments a “one-time use” of federal grants intended for low-income populations.

Chukundi Salisbury, a former South Seattle State House candidate, suggests the city create a permanent fund for traders injured in public projects and lawmakers relax state restrictions.

Although those responsible for the project “sell the dream” that more travelers will enrich small shops, Salisbury said his experience is that “the transport and industrial complex, planners, are interested in lines on a map, in movement cars “. His hairdresser near the construction of the tram in Rainier Valley has gone bankrupt and vacant lots and shops remain, Salisbury said.

Conflicts between short-term business closures and long-term transit growth have played in other American cities and in Vancouver, BC

that of Seattle Department of Economic Development encourages traders to consider consultant assistance and low cost loans. Durkan staff highlighted the city’s new $ 4 million small business stabilization fund, whereby businesses can claim $ 5,000 to $ 20,000 in federal dollars for COVID-related losses.

Some travelers on First Hill this week were unaware or were simply reading the draft from the plastered SDOT signs at intersections. Some are eager to use a faster Madison bus route.

“I would probably consider using public transport again,” said Jess Hancock, the hotel’s guest services representative, who said she was driving instead of making the 45-minute trip in two. bus from Queen Anne.

About 70% of the staff at Virginia Mason Medical Center use public transit or carpooling. “We want to improve and increase transportation to First Hill,†said Facilities Manager Betsy Braun. Besides Line G, she said the subway should preserve Local Route 2 on Seneca Street two blocks north, to ensure easy access for the elderly or other patients who need a stop. bus stop next to the hospital entrance.

The medical center owns the 1000 Madison block, where the master plan would replace old retail storefronts with a hospital up to 240 feet tall.

East of the hill, SDOT will rebuild the entire intersection of Madison Street at Martin Luther King Jr. Way East. Three stopover lanes will be added to allow bus drivers to rest in the valley and then return west.

Six trees will be removed there next to the windows of Coven Salon. There is a risk of losing customers as far away as West Seattle if traffic delays worsen, said Misha Pavesich, guest relations manager at the show. One of the concerns is sidewalk access for people in wheelchairs and walkers, she said, as only one ramp from Madison leads to the barber shop.

“It’s already not an ideal situation,” Pavesich said. In the long term, the improvements to the buses will help show customers and staff who use public transportation, she said.

Outside Vito’s restaurant on Madison, a food delivery driver accommodated already tight spaces, unloading in a nonstop area on Ninth Avenue. Floor manager Stephanie Loose said her regular customers are resilient and they will always reach Vito’s front door.

“We try to be positive about it all. But building is building and Seattle is full of building, and people are aware of that, â€Loose said.